If you are hiring or job searching in behavioral health in 2026, the core story is not a mystery, and it is not hype:

- Demand remains structurally high, driven by persistent mental health and substance use needs and rising expectations for access. Recent national survey reporting continues to show a large share of US adults experiencing mental illness in a given year. [12] (SAMHSA)

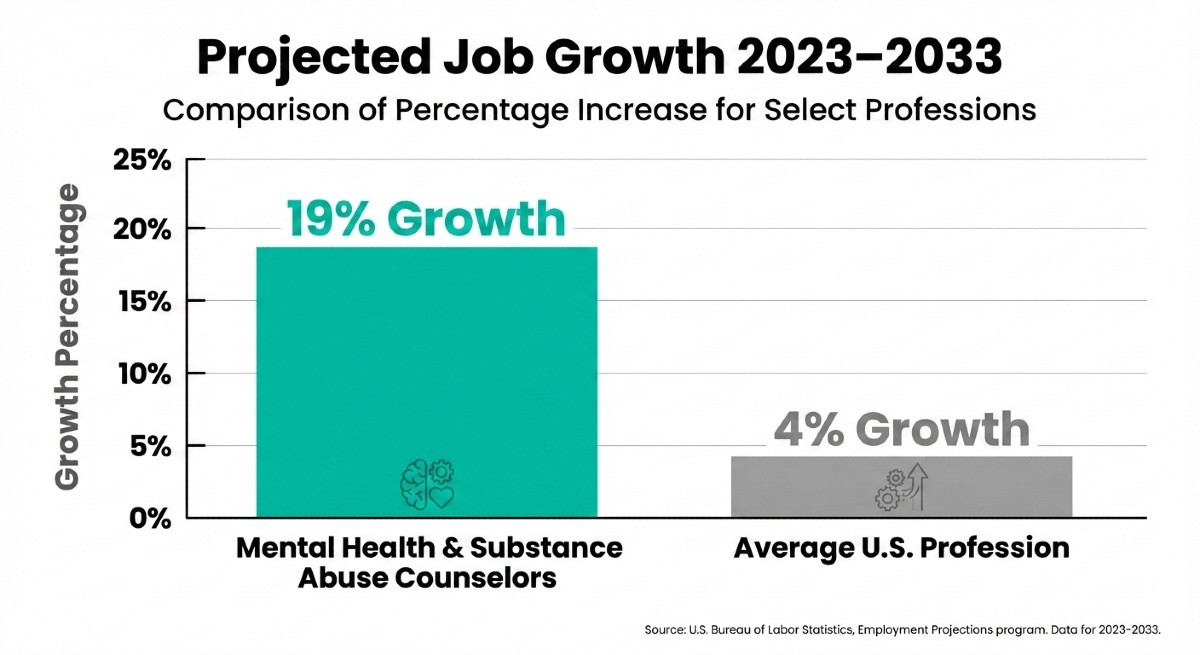

- Many roles are still growing faster than average, especially counseling, technician/aide roles, advanced practice nursing, and healthcare management. For example, BLS projects 17% growth for substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors from 2024 to 2034, with a $59,190 median pay (May 2024). [1] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

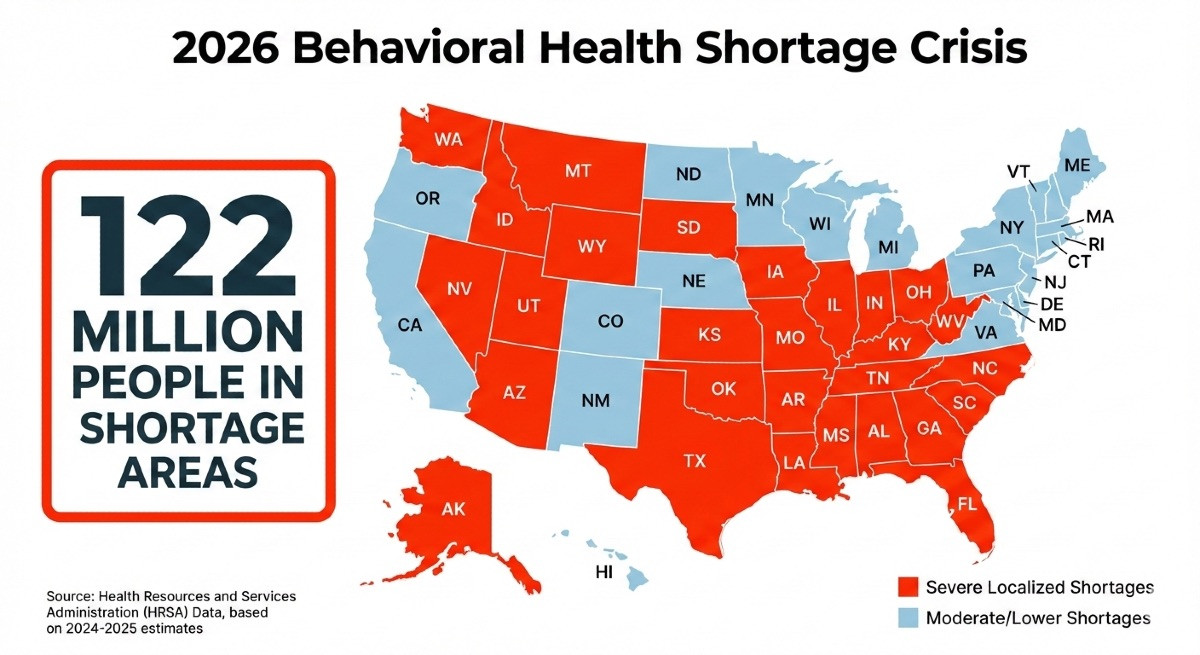

- Capacity constraints remain real, especially by geography and specialty. HRSA summarizes persistent access gaps in shortage areas and highlights rural and county-level scarcity of key clinicians. [10] (Bureau of Health Workforce)

Nearly 130 million Americans live in areas with a shortage of mental health professionals. These workforce shortages, provider shortages, workforce gaps, and critical shortages are creating a national crisis in behavioral health care.

Geographic disparities in mental health provider distribution create 'behavioral health deserts' where residents must travel excessive distances for care.

And in recent years, the demand for mental health services has increased significantly, with service utilization rising from 20% to 23.31% between 2019 and 2022.

Workforce distribution and geographic disparities in provider availability have led to the emergence of 'behavioral health deserts,' where limited access to care is a daily reality for many, especially outside urban centers. The national academy plays a key role in developing strategies and policies to address these shortages and improve access across the United States.

What “2026 outlook” really means: Most government workforce projections are built on multi-year horizons. So a “2026 outlook” is best read as: what conditions are likely to still be true in the near-term, inside the larger 2024–2034 and 2025+ planning picture.

BLS projections show growth trajectories and pay baselines by occupation. [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] (Bureau of Labor Statistics) HRSA’s workforce modeling tools are designed to estimate supply and demand under defined assumptions, which is especially useful for scenario planning. [11] (HRSA Data)

An Introduction to the Behavioral Health Field

The behavioral health field is a cornerstone of the broader healthcare system, dedicated to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders.

Mental health professionals, including mental health counselors, social workers, and psychologists, are at the forefront of delivering essential services that support individuals and communities in need. These professionals play a vital role in promoting mental health, facilitating recovery, and improving overall well-being.

However, the current behavioral health workforce faces significant challenges. There is a persistent shortage of skilled mental health professionals, making it difficult to meet the growing demand for mental health care.

Up to 93% of behavioral health workers have experienced burnout, with nearly half considering leaving the profession.

High rates of burnout and ongoing workforce challenges further strain the system, impacting the ability to deliver quality care. In 2026, the behavioral health workforce is projected to face severe, localized shortages affecting 27 states.

Addressing these issues nationwide is critical to building a resilient behavioral health workforce capable of meeting the needs of diverse populations.

By investing in workforce development and supporting mental health counselors, social workers, and other key providers, the behavioral health field can continue to offer essential services and improve outcomes for those experiencing mental health concerns.

And an encouraging signal, despite the challenges, is the projected job growth of the field, particularly in comparison to other careers, as indicated in the graph below the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and its Employment Projections program.

An Overview of the Behavioral Health System in the US

The behavioral health system in the United States is a complex network that brings together a wide range of organizations, providers, and services to address mental health and substance use disorders.

Care is delivered across various settings, including mental health centers, community health centers, and private practices, each playing a unique role in providing behavioral health services to individuals and families.

Despite its critical importance, the behavioral health sector faces significant barriers that hinder its effectiveness. Workforce shortages remain a pressing issue, limiting access to care and placing additional strain on existing providers. Funding constraints and regulatory challenges further complicate service delivery, making it difficult for organizations to expand access and maintain quality standards.

To address these workforce challenges, it is essential to develop a comprehensive understanding of how the behavioral health system operates, the roles of different provider types, and the obstacles that must be overcome. By doing so, stakeholders can work toward solutions that strengthen the behavioral health sector and ensure that mental health services are available to all who need them.

Demand drivers that still matter in 2026

1) Ongoing mental health and substance use need

A practical employer takeaway for 2026: demand does not need to “spike” to stay high. It can stay high simply by staying broad. National survey reporting continues to show a substantial number of adults experiencing mental illness, and only some are receiving treatment. [12] (SAMHSA)

What this means in hiring terms:

- Continued competition for licensed clinicians (therapy and assessment capacity).

- Strong need for care navigation (case management, community-based supports).

- Higher value on teams that reduce clinician load, especially for documentation, follow-up, and coordination.

Additionally, the behavioral health workforce is facing significant demographic challenges. The provider population is aging rapidly, with a substantial percentage of psychiatrists and other licensed professionals nearing retirement age.

Ongoing attrition - driven by factors such as burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and systemic inequalities, now exceeds the rate of new entrants into the field. This trend threatens the future sustainability of the workforce and underscores the urgent need for trauma-informed support and targeted interventions to address these issues.

2) Crisis demand and access expectations (988 era)

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline has raised public expectations that help should be reachable quickly. SAMHSA publishes ongoing 988 performance metrics for calls, texts, and chats. [13] (SAMHSA) In 2026, this continues to influence staffing across crisis, mobile response, ED diversion, and stabilization settings.

Hiring implications:

- Higher demand for crisis clinicians, call center counselors, and care coordinators.

- More emphasis on handoff workflows, including warm transfers to outpatient and community services.

Workforce shortages often force healthcare providers and emergency departments to limit new patient admissions, directly impacting patient care. Many mental health professionals report no openings for new patients, highlighting a growing access gap.

3) Care shifting to outpatient, community, and integrated settings

Across many markets, more behavioral health care is delivered (or coordinated) in outpatient and community-based environments, including integrated care models. Private practice also offers an alternative setting, with different compensation structures and caseloads compared to public or community-based roles.

The workforce impact is straightforward: more roles are needed in places that are not traditional inpatient psych units, and those settings often need operational depth (scheduling, intake, utilization management, authorizations, and compliance).

4) Autism and ABA demand (limited scope, big local impact)

ABA/autism roles can be highly local and heavily affected by payer policy, school partnerships, and provider footprints.

BLS does not track BCBA/RBT as a single unified occupation the way many employers do, so treat this as a local-market hiring signal rather than a single national statistic. Autism prevalence reporting is one reason demand remains elevated in many communities. [15] (SAMHSA)

Behavioral health workforce shortage: Supply constraints that shape hiring outcomes

1) Supervision and licensure bottlenecks

In 2026, the constraint is often not “people interested in behavioral health.” It is:

- supervised hours,

- qualified supervisors,

- time-to-licensure,

- and role design that protects clinical time.

This is one reason employers who invest in structured supervision, reasonable caseloads, and transparent pay bands often recruit more effectively, even without being the highest payer.

2) Geography and access gaps (rural and underserved areas)

HRSA emphasizes persistent access gaps, including rural shortages and a lack of key clinician types. Underserved regions face particularly acute challenges, with limited access to care for vulnerable populations. [10] (Bureau of Health Workforce)

In 2026, telehealth and hybrid care help, but they do not remove all barriers (broadband, local referral networks, and higher-acuity patients still require local capacity).

3) Role mix and team design

Organizations that treat “licensed therapist” as the only meaningful lever tend to hit ceilings. In 2026, team-based models that intentionally mix:

- licensed clinicians,

- advanced practice providers,

- peer and community roles,

- technicians/aides,

- and strong intake/care navigation are often the models that scale fastest without burning out staff.

The behavioral health workforce is part of the broader human services sector, and workforce diversity and cultural competence are essential for meeting the needs of underrepresented populations. A lack of workforce diversity in mental health services exacerbates access challenges for these groups.

Role families and pathways: what employers hire and what job seekers become

A simple way to organize the 2026 workforce is by care function:

- Assessment and diagnosis: psychologists, psychiatrists, PMHNPs (and sometimes LCSWs, depending on setting). [4][7][9] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Therapy and counseling: LPC/LMHC, LMFT, substance use counselors, and group therapy roles. [1][2] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Care coordination and continuity: social work, case management, care navigation. [3] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- 24/7 and higher-acuity support: psychiatric technicians and aides, crisis staff, residential milieu teams. [5] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Community bridge roles: community health worker and peer-aligned roles that support engagement, follow-through, and access. [8][18] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Operations and leadership: medical and health services managers, program directors, intake leaders, and QA/compliance. [6] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Some behavioral health workforce pathways, such as certain human services and mental health counseling programs, do not require a bachelor's degree for entry, offering flexible options.

Training programs and ongoing career advancement are essential for building a resilient workforce. Training is a lifelong process in behavioral health, supporting professionals in managing emotional labor, preventing burnout, and enhancing cultural competence.

Mental Health Worker Burnout and Support

Burnout among mental health workers is a growing concern within the behavioral health field. Many mental health professionals experience high levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of professional accomplishment.

Factors contributing to burnout include heavy caseloads, limited resources, and a lack of organizational support. These challenges not only impact the well-being of mental health workers but can also affect the quality of care provided to clients.

To address burnout, it is crucial for organizations to prioritize support for their staff. Providing regular clinical supervision, fostering peer support networks, and offering opportunities for ongoing professional development can help mental health professionals manage stress and maintain their effectiveness.

Additionally, reducing administrative burdens and promoting a healthy work-life balance are key strategies for preventing burnout. By creating a supportive work environment, behavioral health organizations can help ensure that mental health workers remain engaged, resilient, and able to deliver high-quality care.

Education and Training Strategies

Developing a skilled and competent behavioral health workforce begins with robust education and training. Mental health professionals require specialized knowledge and practical experience to effectively address the complex needs of their clients.

Key strategies for workforce development include providing supervised clinical experience, which allows trainees to apply their learning in real-world settings under the guidance of experienced supervisors. Continuing education opportunities are also essential, enabling professionals to stay current with best practices and emerging trends in mental health and behavioral health care.

Educational institutions play a pivotal role in addressing workforce shortages by expanding program enrollment, updating curricula to reflect current needs, and offering financial support to students pursuing careers in behavioral health.

By investing in comprehensive training and education, the health workforce can be better prepared to meet the demands of the field and deliver high-quality mental health services across diverse settings.

Leveraging Data and Technology

Harnessing data and technology is increasingly vital for addressing behavioral health workforce challenges and improving mental health services.

Health workforce analysis enables organizations to identify gaps in provider distribution, monitor workforce trends, and make informed decisions about resource allocation. By leveraging data-driven insights, behavioral health organizations can develop targeted strategies to address workforce shortages and improve service delivery.

Technology also plays a key role in expanding access to care and enhancing the quality of behavioral health services. Tools such as electronic health records, telehealth platforms, and data analytics software streamline communication, support care coordination, and enable providers to reach underserved populations.

Training mental health professionals to effectively use these technologies is essential for maximizing their benefits. By integrating data and technology into everyday practice, the behavioral health sector can improve efficiency, reduce costs, and ultimately deliver better outcomes for individuals seeking mental health care.

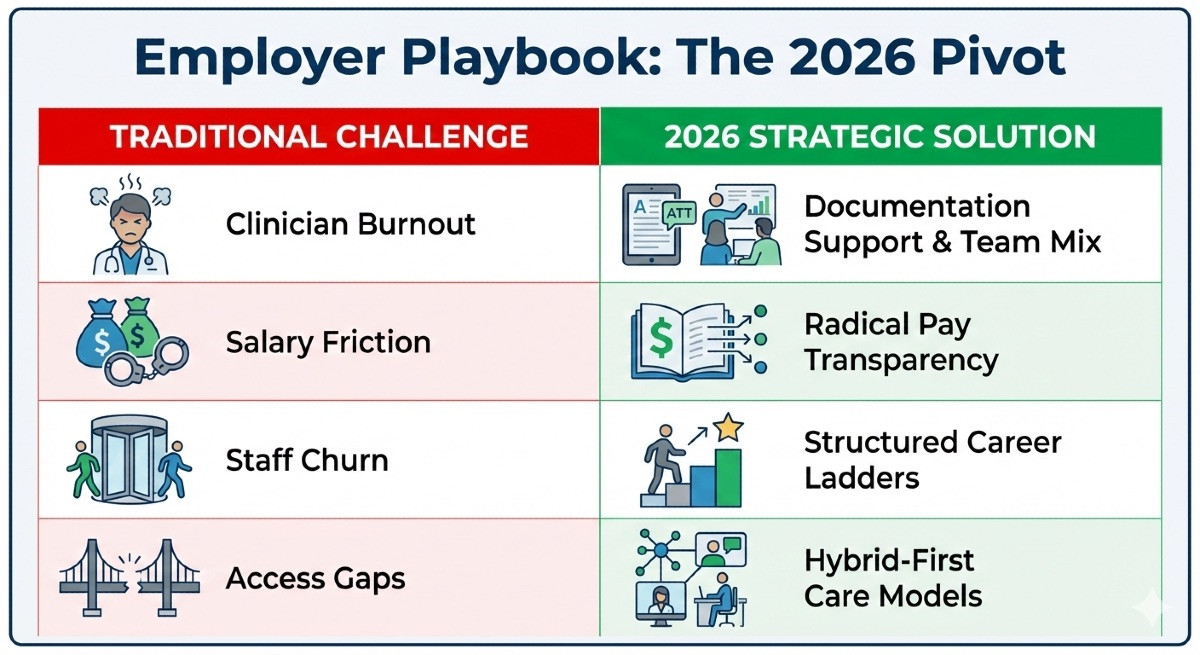

A Behavioral Health Employer Playbook for 2026: 10 actions you can implement

The behavioral health workforce operates as an interdisciplinary team, providing holistic, patient-centered care through collaboration.

To support these dynamic teams, organizations must support providers through trauma-informed practices and comprehensive policies to ensure a resilient behavioral health workforce capable of delivering quality care, especially in high-stress and underserved environments.

- Make salary ranges standard, not negotiable trivia. Use clear bands by role and level. Tie bands to supervision expectations and caseload design. (This is also how you reduce late-stage offer friction.)

- Treat supervision capacity as a production constraint. If you hire pre-licensed staff, budget supervisor time explicitly. Make supervision a scheduled, protected part of the workload.

- Build a retention-first model for high-turnover roles. For tech/aide and intake teams, retention is a staffing strategy. Stabilize schedules, train charge techs, and create ladder steps. Psychiatric tech/aide roles are projected to grow fast, but churn can erase recruiting wins. Addressing burnout is essential for improving workforce retention, building a sustainable workforce, and delivering quality care. [5] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Design roles to protect clinician time. Offload non-clinical tasks with strong intake, documentation support, and care coordinators. Supporting clinical care in this way helps prevent burnout and maintain workforce sustainability.

- Use telehealth and hybrid intentionally (not as a perk). Define what is remote-eligible, how handoffs work, and how you maintain clinical quality and team cohesion.

- Offer licensure support that is concrete. Examples: paid supervision, exam fee reimbursement, study time, differential pay for newly licensed staff.

- Use loan repayment pathways as a recruiting lever (where eligible). Know which roles qualify and how to message it responsibly. HRSA programs such as NHSC loan repayment can apply to eligible behavioral health clinicians depending on site and discipline requirements. [16] (National Health Service Corps) HRSA’s STAR program is another federal loan repayment program tied to SUD treatment workforce needs. [17] (SAMHSA)

- Hire for team mix, not only individual credentials. Combine licensed therapy capacity with community bridge roles and peer-aligned support where appropriate. SAMHSA describes peer support specialist roles and how they support recovery-oriented systems. [18] (HRSA Data)

- Add career ladders for “toward the middle” roles. Intake leads, UR/auth specialists, case management leads, group facilitators, and clinical documentation excellence tracks reduce dependence on a single role category.

- Upgrade leadership early. Healthcare management roles are projected to grow rapidly, and strong ops leadership often unlocks access capacity (faster intake, better scheduling, cleaner utilization management). [6] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Job Seeker Game Plan for 2026: 10 moves that improve outcomes

Workforce gaps and shortages of behavioral health professionals and healthcare providers create both challenges and opportunities for job seekers in the behavioral health workforce.

Understanding these dynamics is key to advancing your career and meeting the needs of diverse communities.

Our Top Pair of Suggestions

- Pick a pathway with a timeline. If you are choosing between counseling, social work, and MFT tracks, map the steps: degree, supervised hours, exam, licensure. Small differences affect earning power and mobility.

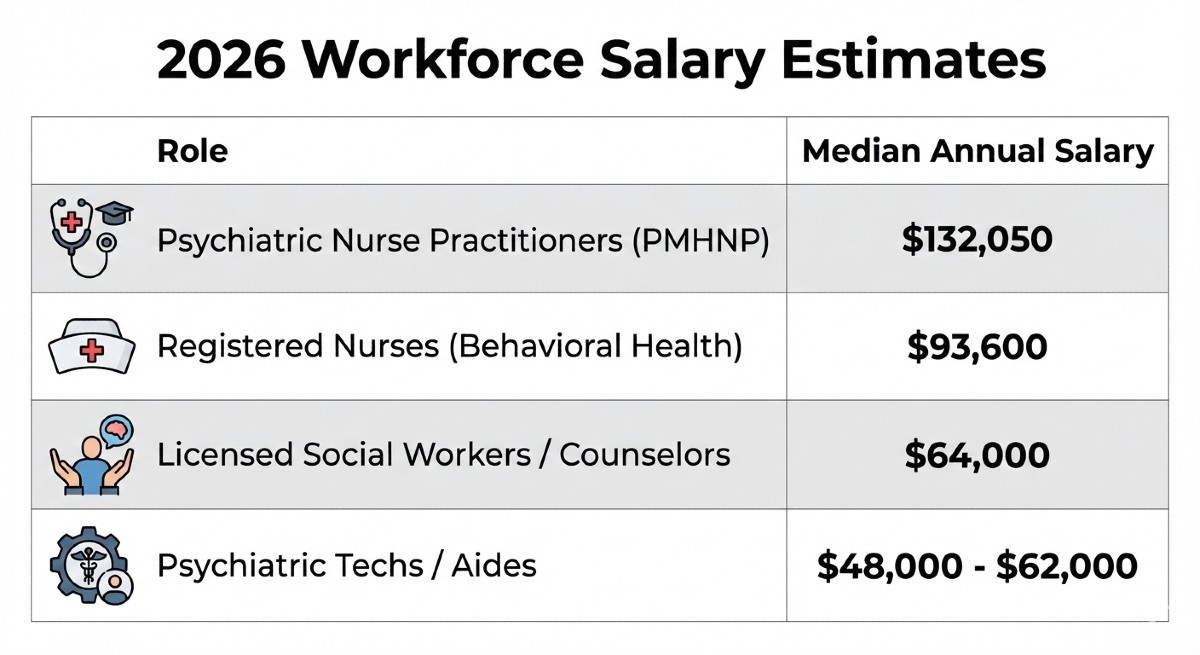

- Use labor-market baselines, then localize. BLS provides national pay medians and projected growth for major roles. For example:

- Counselors: $59,190 median pay; 17% outlook [1] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Social workers: $61,330 median pay; 6% outlook [3] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Psychologists: $94,310 median pay; 6% outlook [4] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Additional salary estimates from the BLS are shown below.

Our Magnificent 8: Additional Suggestions to Enhance Your Search

- Choose supervision like you choose a manager. Ask: frequency, structure, documentation expectations, and how caseload ramps over the first 90 days.

- Optimize setting fit, not only title. Outpatient therapy, IOP/PHP, residential, crisis, MAT programs, and integrated care all build different skills and tolerance for intensity.

- Negotiate the full package, not only base pay. Look at: productivity requirements, cancellation policy impact, paid documentation time, training support, and licensure costs.

- Use role stacking to grow faster. Examples: intake + care coordination, group facilitation + SUD credentialing, bilingual capability + crisis training.

- Know where advanced practice demand is strongest. APRN roles have very high projected growth overall, which can translate into strong market pull for PMHNP pathways in many regions. [7] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Evaluate burnout risk as a job factor. Ask about caseload, acuity, no-show handling, after-hours expectations, and whether your schedule is controllable.

- Consider community bridge roles as entry points. Community health worker roles are projected to grow, and they can be a stepping stone into care navigation, case management, and some clinical pathways depending on education goals. [8] (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Treat location strategy as career strategy. In 2026, CA/NY/NJ/FL/TX metros can be opportunity-rich, but competition is real. If you can work hybrid or relocate within a state, your option set expands. However, workforce shortages of behavioral health professionals and healthcare providers disproportionately affect marginalized communities, leading to disparities in access to mental health care.

When you are ready to compare settings and pay, search mental health treatment careers and addiction treatment careers that publish salary ranges so you can negotiate from evidence.

What we’re watching in 2026: Scenarios, not predictions

- Access scenario: If access expectations continue rising (including crisis-connected pathways), employers who invest in intake speed and follow-up capacity will pull ahead. 988 performance metrics remain a useful signal to monitor for system demand. [13] (SAMHSA)

- Workforce supply scenario: HRSA’s workforce modeling and research briefs continue to highlight long-run shortage pressure and geographic gaps. The behavioral health workforce shortage is now recognized as a severe and critical workforce shortage, with Mental Health America emphasizing the urgent need for systemic reforms and innovative solutions to address these disparities. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically accelerated and intensified these workforce challenges, further exacerbating the severe shortage of mental health professionals. If those gaps persist, 2026 competition will remain high even in moderate-growth occupations. [10][11] (Bureau of Health Workforce)

- Financing scenario: If payer and public funding shifts favor outpatient and community models, demand may tilt further toward care coordination, peers, and tech-enabled workflows rather than only adding licensed therapy hours.

- SUD trend scenario: If overdose mortality continues its recent decline (as indicated in CDC reporting), workforce needs may shift by region and program type, but treatment and recovery services will still require sustained staffing. [14] (CDC)

- Autism/ABA scenario: If autism-related service demand remains elevated, local labor markets for ABA/autism roles may stay tight, affecting schools, clinics, and home-based services. [15] (SAMHSA)

The Key Takeaways for 2026

- For employers, the 2026 advantage is often operational: supervision capacity, pay transparency, retention design, and role mix.

- For job seekers, the advantage is market literacy: pathway planning, supervision quality, and selecting roles with sustainable workloads and transparent compensation.

Related Resources for Job Seekers and Employers

- Peer Support Specialist Career Guide

- Behavioral Health Nursing Career Guide

- Mental Health Counselor Career Guide

- Our Careers in Behavioral Health Guide

Sources

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Substance Abuse, Behavioral Disorder, and Mental Health Counselors (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[2] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Marriage and Family Therapists (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[3] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Social Workers (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Psychologists (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Psychiatric Technicians and Aides (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[6] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Medical and Health Services Managers (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[7] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Nurse Anesthetists, Nurse Midwives, and Nurse Practitioners (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[8] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Community Health Workers (2024 median pay; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[9] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Physicians and Surgeons (pay floor; 2024–34 outlook). (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

[10] Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Bureau of Health Workforce. State of the Behavioral Health Workforce, 2025 (research brief). (Bureau of Health Workforce)

[11] HRSA, Bureau of Health Workforce. Workforce Projections Dashboard and Behavioral Health Care Provider Model Components (methods and assumptions for supply/demand modeling). (HRSA Data)

[12] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2023 NSDUH Annual National Report and Highlights (mental illness and treatment indicators). (SAMHSA)

[13] SAMHSA. 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline Performance Metrics (ongoing system demand and contact volumes). (SAMHSA)

[14] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts / overdose mortality reporting (trend context). (CDC)

[15] CDC. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network reporting (autism prevalence context). (SAMHSA)

[16] HRSA. National Health Service Corps Loan Repayment (eligibility and program overview). (National Health Service Corps)

[17] HRSA. STAR Loan Repayment Program (SUD workforce-focused loan repayment). (SAMHSA)

[18] SAMHSA. Peer Support Specialist (role definition and workforce context). (HRSA Data)